Table of Contents

Toggle

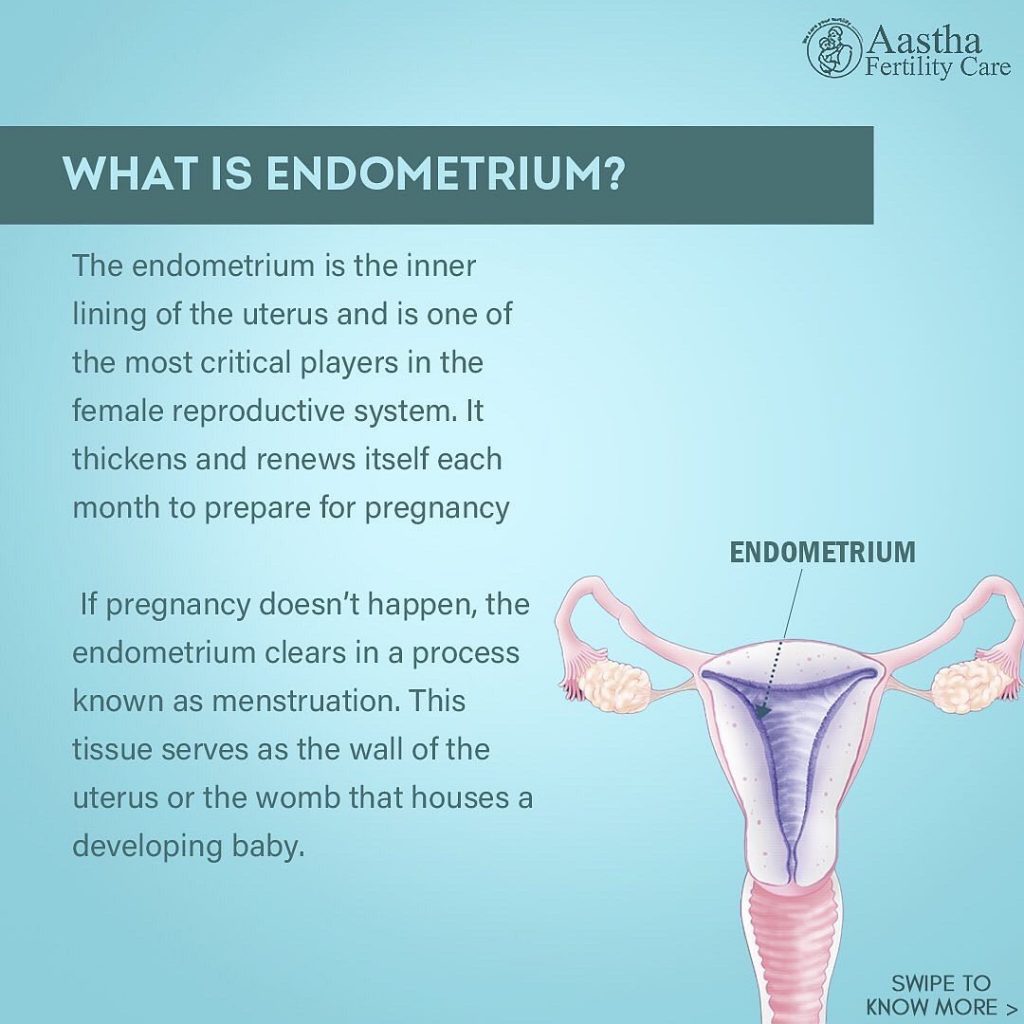

The endometrium is the inner lining of the uterus and is one of the most critical players in the female reproductive system. The endometrium thickens and renews itself each month to prepare for pregnancy. If pregnancy doesn’t happen, the endometrium clears in a process known as menstruation. This tissue serves as the wall of the uterus or the womb that houses a developing baby.

The endometrium has layers. During the menstrual cycle, the second layer fluctuates depending on what stage a woman is at in her cycle. In contrast, the first layer serves as a stabilizing anchor in the uterus and remains unchanged. The fertilized egg or a blastocyst will be implanted at this functional layer of the endometrium if conception occurs. The endometrium changes every month in preparation for the arrival of an embryo.

The dynamic layer of the endometrium is responsible for controlling a woman’s period and menstrual cycle. Many problems can arise when trying to become pregnant if the endometrium is abnormal or dysfunctional. The most common problems in the endometrium are a displaced window of implantation and endometriosis. The other conditions that could occur in the it include endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

How the Endometrium Works

The uterus has three layers: the serosa, the endometrium, and the myometrium. The serosa is the outer layer of the uterus, which secretes a watery fluid to protect against friction between the uterus and nearby organs.

The other layer is the middle uterine layer, known as myometrium— the thickest layer of the uterus, made up of thick, smooth muscle tissue. The myometrium expands during pregnancy to house the growing baby. Contractions of the myometrium during labor assist in the birth.

Endometrium makes up an inner lining of the uterus that varies in thickness throughout the menstrual cycle. The endometrium itself has three layers:

- Stratum basalis: This is the deepest endometrial layer, also known as the basal layer. It sits against the myometrium and does not change much throughout the cycle. Consider it the base from which the changing layers of the endometrium grow.

- Stratum spongiosum: This is an intermediate layer of the endometrium that is spongy.

- Stratum compactum: This outer layer of the endometrium is thinner and more compact compared to the other endometrial layers.

The stratum spongiosum and stratum compactum layers change dramatically throughout the menstrual cycle. Together, these layers are known as the stratum functional or functional layer. The functional layer goes via three primary stages in each cycle.

Proliferative Phase

In this phase, the endometrium thickens to prepare the womb for an embryo. This stage commences on the first day of menstruation and persists until ovulation. Estrogen is crucial to the formation of a healthy endometrium. Endometriums that are too thin or too thick can result from estrogen levels that are too high or too low. During this time, the endometrium also becomes vascularized through straight and spiral arteries. These arteries supply necessary blood flow to the endometrium.

Secretory Phase

The endometrium starts to secrete essential nutrients and fluids in this phase. Progesterone is the crucial hormone for this phase. This phase commences after ovulation and persists until menstruation. The glands of the endometrium secrete proteins, glycogen, and lipids. These materials nourish an embryo and prevent the endometrium from breaking down.

If an embryo implants itself into the endometrium wall, the developing placenta will begin to secrete a human chorionic gonadotropic hormone (hCG). To maintain the endometrium hCG hormone then signals the corpus luteum (on the ovaries) to keep producing progesterone.

Also, with progesterone withdrawal, the spiral arteries that supply the endometrium with blood flow start to constrict. It then leads to the breakdown of the functional layer of the endometrium. Finally, the endometrium is discharged from the uterus through menstruation, and the cycle starts again.

Menstruation and Pregnancy

The functional layer of the endometrium goes through specific changes just before ovulation. Tiny blood vessels proliferate(vascularization), and uterine glands become longer.

As a result, the endometrial lining thickens and becomes enriched with blood, so it can receive a fertilized egg and support a growing placenta. The placenta is an organ that develops during pregnancy to supply a fetus with oxygen, nutrients, and blood. In the absence of conception, the build-up of blood vessels and tissues is not needed and is shed, resulting in periods. The endometrial linings will stay relatively thin and stable in young girls who haven’t gotten periods and adults who’ve gone through menopause.

How will my endometrium affect me?

Endometrium plays a significant role in your ability to get pregnant. Implantation will not occur if the endometrium is not ready to accept a fertilized egg, and you will be unable to get pregnant. In otherwise healthy women, recurrent implantation failure(RIF) is one of the major causes of infertility. The reason behind RIF could be issues involving the uterus, the embryo, or the environment in which both interact (the endometrium). Infections affecting the endometrium may affect your fertility, which could be influenced by several factors, including how thick or thin your endometrium is infected and the bacteria present in the tissue.

Endometrial Conditions

If you menstruate, you probably know that the ebb and flow of the endometrial lining is largely predictable. However, this can change due to abnormalities of the endometrial lining. The following are the most common conditions women may experience.

Endometriosis

Sometimes endometrial lining can migrate out of the uterus’s borders as it thickens and grows on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or the tissue lining the pelvis. Even though it’s outside the uterus, this tissue will continue to grow and break down as you menstruate. The problem is that the blood and tissue have nowhere to exit the body and become trapped because it is displaced. As a result of endometriosis, cysts on the ovaries called endometriomas, scar tissue, and adhesions can develop, which causes structures in the pelvis to stick together.

The primary symptom is severe pain during menstruation, intercourse, urination, or bowel movements. You might experience heavy periods, feel extra tired, nauseous, or bloated.

Many medications, hormone therapy, or surgery are available to treat endometriosis.

Endometriosis can result in some degree of infertility in roughly 40% of women, whether due to scar tissue and adhesions in the fallopian tubes or too low levels of progesterone that can affect the way the uterine lining builds, also known as luteal phase defect.

Endometrial Hyperplasia

This condition happens due to a specific hormonal imbalance, causing too thick endometrial lining. In the absence of ovulation, the endometrium can thicken due to an excess of estrogen combined with an absence of progesterone. The endometrial lining isn’t shed, and cells inside it continue to increase under these conditions.

Endometrial hyperplasia can occur during perimenopause or after menopause. The condition can also occur in people who take medications that mimic estrogen (without progestin or progesterone) or take high doses of estrogen for a prolonged period after menopause. Other complications are irregular menstrual periods, particularly in people with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), infertility, or obesity. In the case of endometrial hyperplasia, the excess cells can become abnormal and put you at risk for endometrial cancer.

Cancer

The growth of abnormal cells causes endometrial cancer. About 90% of people diagnosed with this condition have abnormal vaginal bleeding. Other possible symptoms of endometrial cancer include:

- Non-bloody vaginal discharge.

- Pelvic pain.

- Feeling a mass in your pelvic area.

- Unexplained weight loss.

If your periods change dramatically or you have bleeding between periods or after you go through menopause, consult your doctor. These symptoms can be caused by less serious conditions, but it’s better to be safe than sorry.

Leave a comment